We live in southern New Jersey in a rural farmland area of Cape May County. Much of my experience with native plants and wildlife habitat gardening is based here. But the logic and the concepts are applicable nationwide and even worldwide. I have presented programs and taught workshops about wildlife gardening all over the country.

Our wildlife garden dates back to 1977 when we purchased our half-acre property. There was no landscaping except for an old Lilac bush and Day Lilies around the front porch of our 1845 farm house. The person we purchased the property from apologized that his bulldozer had broken down and he hadn’t been able to level the woods in the back third of the property. Thank God, we thought.

Even before unpacking, we began planning and planting our wildlife habitat.

Today, 48 years later, our half-acre property shelters 202 species of native plants: 127 species of native perennials (and one native annual: Partridge Pea), 61 species of native trees, shrubs, & vines, 9 species of native grasses, and 5 species of native ferns.

Living Fence for Wildlife and Privacy

We had two dogs, English Setters, so of necessity we enclosed the open part of the backyard with a 6′ high chain-link fence. We then chose the sunniest part of the backyard within the chain-linked area and fenced it off from the dogs as our vegetable garden. We let vines and tree seedlings grow up and through the fence, cherishing the privacy it gave us. New neighbors to either side each attacked the growth on their side of our fence (which we’d placed well within our property line, by the way!). Eventually they ran out of steam, thankfully, and today’s living fence (a hedgerow really) gives our backyard a feel of complete privacy far from neighbors, even though they’re a whisper away.

Over the years as I learned more and more about wildlife gardening and as I (very slowly in the 1970s and early 1980s) found gem native perennials, I began tucking them into our garden until eventually there was little room left for vegetables. With the proliferation of roadside farm stands and with Jersey Fresh produce available nearby, it seemed to make more sense to grow pollinators instead. Our entire garden is on our septic field, so it is full of perennials but no shrubs or trees.

In 1977 and 1978, Clay chose not to mow the backyard to the left of the vegetable garden to see what might come up. An American Holly and a Georgia Hackberry tree both sprouted from bulldozed roots. Today they are beautiful and sizable trees.

The Best Time to Plant a Tree

In 1984, I planted a Tulip Tree because I love this native and because Tiger Swallowtails lay their eggs on its leaves. It was only a foot tall. I told Clay that eventually it would shade the house. “Right,” he said sarcastically as he looked down at this bit of a thing that was no bigger than a ruler. Today he eats his words as the 60′ tall Tulip Tree towers over our roof.

At the same time I planted some White Pines that I found as 3″ tall seedlings coming up in the gravel pit behind our property. Today they too reach to the sky but have lost most of their lower branches due to heavy snows and winds. I wish I’d known then what I know now and instead planted Red Cedars that, being more local to South Jersey, would have better stood the test of time. If you haven’t guessed it yet, the best time to plant a tree is twenty years ago.

Gifts From the Birds

Many of the trees on our property were planted by the birds, including dozens of Georgia Hackberries, Red Maples, Red Cedars, Black Cherries, Persimmons, Sweet Gums, and American Hollies, all because Clay paid attention and chose to mow around tree seedlings rather than obliviously cut them down.

Our Wildlife Ponds

We’ve had wildlife water features since the 1980s. Our first “ponds” were old cast iron bathtubs that we placed deep in the ground. They were free (sitting on a curb for pick up) but not ideal for wildlife due to their steep sides. We created our next pond with a flexible rubber liner. I planted Cattails because they’re native and because Ruby-throated Hummingbirds use the fluff from dispersing Cattail seed heads in nests. But this was a big mistake for a small pond! The Cattail roots outgrew the pot and filled the pond to the degree that we could walk across it. I tried to dig them out but ended up putting a hole in the liner. In the end it became a sometimes-wet bog.

Today our ponds are care-free lightweight, molded semi-rigid preformed ponds made with high density polyethelene and we’ve never looked back. Over the years we’ve documented a whole host of frogs and toads, dragonflies and damselflies, and many other water-loving critters using our ponds. Many visitors to our gardens sprint out to the ponds to see who is at home. No one is ever disappointed; something is always going on.

Plant Wars

In the Spring of 2009 we tackled our woods, the back third of the property. With years of working full time for long hours, we lost track of what was happening back there. The area had been consumed by an impenetrable, 12′ high, dense stand of nonnative, invasive Multiflora Rose and Japanese Honeysuckle. Clay had mowed a winding path through it for years, but it was impossible to venture off the path.

In 2009, we hired a young and muscular landscaper. In one day he successfully cut down and ground up the Multiflora Rose and Japanese Honeysuckle, using a brush hog. Prior to letting the landscaper have at it, we flagged all the live and dead trees we didn’t want him to touch.

After he laid waste to the wall of invasives we dug out the roots or very judiciously spot-treated new growth with Roundup. As soon as sunlight could reach the forest floor, a seed bank of natives began to flourish. Each day brought new surprises.

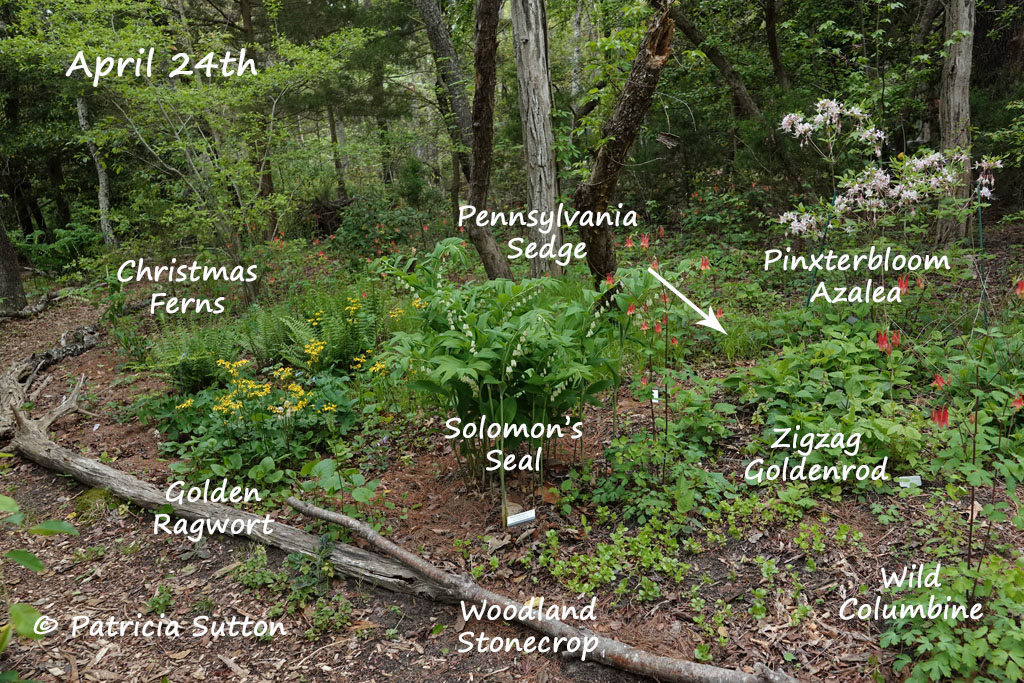

Walking through fifteen years after the invasives were cleared, is like walking through a natural nursery. The birds have planted so many trees, shrubs, and vines. Willow Oaks planted as acorns by Blue Jays are taller than two tiny seedlings friends gifted to me in 2011. It took Winged Sumac nine years to show up naturally in our woods.

We’ve lined our woodland path with fallen branches and tree trunks. This abundance of dead wood is home to many pollinators and other life. Today there is a thriving understory of native perennials, grasses, shrubs, and young trees in our woods.

I love the sunlit perennial garden, but our woods are my “Happy Place.” Spring comes early in the woods, and summer days are cooler there. It is where we always hear hummingbirds chittering. One day I’ll find their nest.

Shade Gardens Instead of Lawn

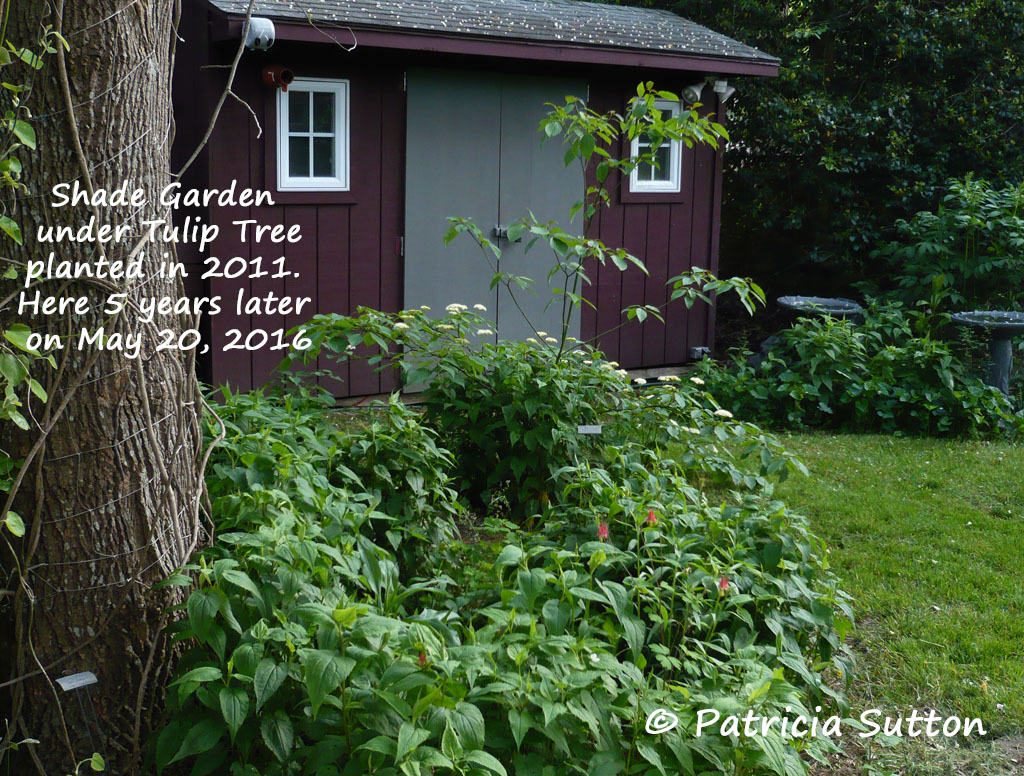

In 2011 we planted shade-loving native perennials (Wild Columbine, Jacob’s Ladder, Common Blue Wood Aster, and Lyre-leaved Sage) and shrubs (American Strawberry Bush and Alternate-leaf Dogwood) under the now-towering Tulip Tree.

Since then these native perennials have seeded and spread further and further into the lawn area and the shrubs have flourished. Now, rather than boring lawn under the Tulip Tree we have a nectar and seed-rich layered landscape that also provides important cover for wildlife.

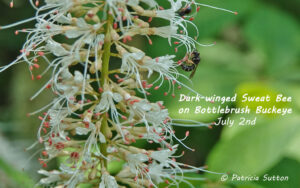

Today shade gardens are not limited to the area under our Tulip Tree or in our woods. They have filled all the edges of our property and spill out into the yard (or what was once yard). It has been great fun to add additional native shrubs (like the blooming Bottlebrush Buckeye below) to edges and plant each with an understory of shade-loving perennials. Today our lawn is limited to pathways through pollinator gardens.

Lose the Lawn, Create a Meadow Instead

In 2012 Clay stopped mowing a sunny portion of the backyard (his goal is to eliminate all mowing) where we wanted to create a “Pocket Meadow.” I sped up the process by plugging the area with meadow plant seedlings from our garden (Purple Coneflower, Common Milkweed, Butterfly Weed, Little Bluestem, and Indian Grass).

Since then I’ve continued to complement the small meadow with additional native grasses and wildflowers, all made easier by the existence of some NEW local native plant nurseries.

Two New Native Shrubs Once the Lilacs Came Out

With new local native plant nurseries, I was captivated by some native shrubs I hadn’t been aware of previously. In 2016, I cut down our ancient, non-native Lilacs out front because they were flowering so sparsely and because I needed those sunny spots for my two new acquisitions. White Fringetree and Common Ninebark waited patiently in pots another year until I finally dug the last of the Lilac roots out (early in 2017). What a beast of a job that was, but well worth it.

White Fringetree begins blooming around May 1st. Here it is on May 7, 2023, when seven years old. Each spring I eagerly look forward to its intoxicating fragrance and dainty flowers.

Common Ninebark, in the rose family, blooms by mid-May. Here it is on May 15, 2023, when seven years old. Its flowers are stunning and very important to early-season pollinators, like this native Blueberry Digger Bee.

If you are lucky enough to have native plant nurseries near you too, may your property continue to evolve with additional native plants that fill each week with a variety of nectar offerings, host plant options, fruit selections, etc. I’ve pretty much filled every nook and cranny with native plants now. One of these days, when Clay is otherwise occupied, I’ll probably dig out the last holdout, Flowering Quince (native to northeast Asia), and have room for one more delightful and beneficial native.

Wildlife Benefiting From Our Habitat

Our little half-acre in Cape May County has attracted 213 different birds and 79 different butterflies since 1977. That is pretty remarkable.

But a real scare in the last 7 or so years (since at least 2018) has been a drastic drop in diversity and numbers of butterflies (and moths), despite Pat continually adding to their property’s offering of native nectar & host plants.

Fortunately, other pollinators (bees, wasps, flies, day-flying moths, and beetles) caught Pat’s fancy. They seemed to be abundant, but in reality, they too are probably far fewer during today’s “Insect Crisis,” than they once were. Pat readily admits that “in the good old days, we were so dazzled by the clouds of butterflies dashing about the garden that we paid little attention to the other pollinators.”

With less travel during the Pandemic, Pat explored her wildlife gardens almost daily, savoring the myriad of native plants and the many pollinators attracted to them. In previous years she’d dabbled at learning bees, wasps, etc., but they are tough! With the help of iNaturalist and Heather Holm’s book Wasps, she earnestly studied the pollinators benefiting from her wildlife habitat.

Late in 2023, Pat was given hope (and great joy) when she tallied up the pollinators (beyond butterflies) benefiting from their diverse ½ acre property. As of April 2025, she has photographed and documented 117 pollinators (beyond butterflies), including: 37 species of wasps, 34 species of flies, 27 species of bees, 10 species of beetles, and 10 species of diurnal moths nectaring in the gardens. Oh, and she still has a zillion more photos to submit to iNaturalist and figure out! So, the project is ongoing. You can check out Pat’s iNaturalist sightings HERE , then click on “Sightings.” Who knew that flies were SO COOL and so beautiful ? ! ! ! !

A Work in Progress

Our wildlife garden has been evolving since the beginning. As we keep learning it keeps progressing. With locally grown native plants now more readily available than they were for the first 30 years of our gardening efforts, the transformation of the garden has sped up.

With so many years of trial and error, I now use my wildlife gardens (during the workshops I teach and the garden tours I lead) as teaching tools to help spare others the growing pains that Clay and I experienced.

We are proud that our wildlife habitat was chosen as one of 15 “Birdy Backyard All-Stars” featured in Bill Thompson III’s book, Bird Homes and Habitats (published in 2013), and was one of 29 gardens featured in Nancy Berner and Susan Lowry’s Gardens of the Garden State (published in 2014).