For two solid months (July 9th through September 8th) we enjoyed 1-4 Monarchs daily in our 47-year-old wildlife garden, many days including a female (or two) laying eggs. We saw our 1st Monarch on May 26th, then another on July 1st. On July 9th we spotted a female laying eggs, and the rest is history.

Our neighborhood may be more of a Monarch oasis than many neighborhoods because our wildlife garden harbors so many milkweed plants (over 100) and because I have milkweed scattered around our half acre, not all in one or two spots, and because we have a few nearby wildlife gardening neighbors with loads of milkweed . Garden strolls this summer and early fall included finding multiple eggs, tiny newly-hatched caterpillars, and large caterpillars. Even now, as I write this on September 18th, I am still finding multiple caterpillars (some small and some about to pupate). We have not found a chrysalis . . . YET, but that doesn’t keep us from looking.

Our neighborhood may be more of a Monarch oasis than many neighborhoods because our wildlife garden harbors so many milkweed plants (over 100) and because I have milkweed scattered around our half acre, not all in one or two spots, and because we have a few nearby wildlife gardening neighbors with loads of milkweed . Garden strolls this summer and early fall included finding multiple eggs, tiny newly-hatched caterpillars, and large caterpillars. Even now, as I write this on September 18th, I am still finding multiple caterpillars (some small and some about to pupate). We have not found a chrysalis . . . YET, but that doesn’t keep us from looking.

Our milkweed offerings are plentiful, including:

Butterfly Weed Several plants return each spring, but are not that happy in our richer-than-they-would-like soil. This native milkweed much prefers sand, gravel, bone-dry sites, and railroad beds, hence it’s other common name, Railroad Annie.

Eastern Swamp Milkweed Seven plants return each spring in my rain gardens, where hose ends empty out our rain barrels. This native milkweed is stunning and a magnet to all pollinators. By September, their leaves are pretty much dried up and not looking their best, but I leave all in place for wildlife!

Common Milkweed Over one hundred plants are scattered throughout the sunny (and not so sunny) perennial garden, meadow, and vegetable garden. Many consider this milkweed to be a thug because it sends underground runners and pops up in entirely new sites like garden paths, lawn areas, other garden beds. For years I dug up these wayward milkweeds and substantial portions of their roots so I could give them away. Now I cherish each outlier because these outliers are less likely to attract as many predators. Monarch eggs and caterpillars on outliers seem to have a better chance of surviving. This native milkweed is a hotbed of Monarch activity. It blooms in late June / early July. Its fragrance is intoxicating and its huge pale pink balls of flowers steal the show and draw in many, many pollinators. By August and into October (and sometimes even through November), its leaves are still robust and being used by resident Monarchs as they lay one last batch of eggs before dying. These late-season eggs, if frosts hold off, result in one last generation of migratory Monarchs on the Cape May Peninsula (where the warm waters of the Atlantic Ocean and the Delaware Bay sustain micro habitats of pleasant weather).

Common Milkweed Over one hundred plants are scattered throughout the sunny (and not so sunny) perennial garden, meadow, and vegetable garden. Many consider this milkweed to be a thug because it sends underground runners and pops up in entirely new sites like garden paths, lawn areas, other garden beds. For years I dug up these wayward milkweeds and substantial portions of their roots so I could give them away. Now I cherish each outlier because these outliers are less likely to attract as many predators. Monarch eggs and caterpillars on outliers seem to have a better chance of surviving. This native milkweed is a hotbed of Monarch activity. It blooms in late June / early July. Its fragrance is intoxicating and its huge pale pink balls of flowers steal the show and draw in many, many pollinators. By August and into October (and sometimes even through November), its leaves are still robust and being used by resident Monarchs as they lay one last batch of eggs before dying. These late-season eggs, if frosts hold off, result in one last generation of migratory Monarchs on the Cape May Peninsula (where the warm waters of the Atlantic Ocean and the Delaware Bay sustain micro habitats of pleasant weather).

Tropical Milkweed Each spring I purchase 4-5 plants at nearby Goshen Gardens nursery. I tuck this non-native annual milkweed into a few spots in my yard, including out front where I have no other milkweeds. Being an annual this milkweed blooms and blooms and continues to bloom right up until the first frost. It is a favorite of Monarchs for nectaring and egg-laying. September 7th I set up a study station for two young home-schooled naturalists. They discovered an egg and multiple caterpillars on two plants.

Tropical Milkweed Each spring I purchase 4-5 plants at nearby Goshen Gardens nursery. I tuck this non-native annual milkweed into a few spots in my yard, including out front where I have no other milkweeds. Being an annual this milkweed blooms and blooms and continues to bloom right up until the first frost. It is a favorite of Monarchs for nectaring and egg-laying. September 7th I set up a study station for two young home-schooled naturalists. They discovered an egg and multiple caterpillars on two plants.

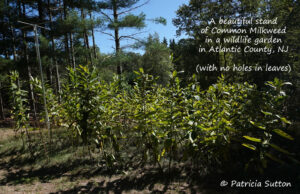

I had hoped that my own garden was an indicator that it was a good Monarch year. But I was in several milkweed-rich gardens on September 8, 2024. These gardens (in Atlantic County and Gloucester County) were part of a tour of Native Landscapes in South Jersey, organized by the SE Chapter of the Native Plant Society of NJ. The tour and the properties were inspirational. Each site was unique and offered great learning opportunities. But, I saw zero holes in milkweed leaves in the prolific patches. Huh! It was a shock to see so much untouched milkweed (without holes in the leaves). The garden owners shared that they had seen very few Monarchs so far this year.

I had hoped that my own garden was an indicator that it was a good Monarch year. But I was in several milkweed-rich gardens on September 8, 2024. These gardens (in Atlantic County and Gloucester County) were part of a tour of Native Landscapes in South Jersey, organized by the SE Chapter of the Native Plant Society of NJ. The tour and the properties were inspirational. Each site was unique and offered great learning opportunities. But, I saw zero holes in milkweed leaves in the prolific patches. Huh! It was a shock to see so much untouched milkweed (without holes in the leaves). The garden owners shared that they had seen very few Monarchs so far this year.

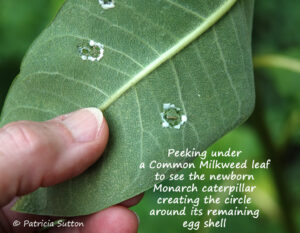

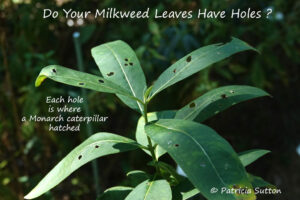

In comparison, my milkweed leaves are full of holes! You might not realize this, but when the tiny Monarch caterpillar hatches from its egg, its first meal is what remains of its egg shell. Then it cuts through the leaf in a nice neat circle around the egg to get the milkweed milky sap (known as latex) to flow . The bit of leaf in the center of this circle is now latex free and safe for the tiny newborn Monarch caterpillar to eat . Elizabeth Howard / Journey North has a beautifully written and illustrated graphic on this topic: “Let’s Find Monarchs! Clues in the Milkweed Patch.”

In comparison, my milkweed leaves are full of holes! You might not realize this, but when the tiny Monarch caterpillar hatches from its egg, its first meal is what remains of its egg shell. Then it cuts through the leaf in a nice neat circle around the egg to get the milkweed milky sap (known as latex) to flow . The bit of leaf in the center of this circle is now latex free and safe for the tiny newborn Monarch caterpillar to eat . Elizabeth Howard / Journey North has a beautifully written and illustrated graphic on this topic: “Let’s Find Monarchs! Clues in the Milkweed Patch.”

Maybe the key to more Monarchs is having a few nearby neighbors who are also wildlife gardeners, so your own offerings are not the only show in town. And if you do have milkweed, be sure to have lots of it and scatter it around so that predators can not find every last egg and caterpillar. Predators are drawn to our wildlife gardens and all the life we’ve attracted. Predators are hungry too and a Monarch caterpillar is a choice meal for a paper wasp to carry back to its nest.

Time will tell if summer Monarch numbers were good. They were in my garden; I still had 7 full grown caterpillars yesterday (September 17th), and that was without even peeking under all the leaves. But, as I learned just recently, even a county or two away they were absent.

Time will tell if summer Monarch numbers were good. They were in my garden; I still had 7 full grown caterpillars yesterday (September 17th), and that was without even peeking under all the leaves. But, as I learned just recently, even a county or two away they were absent.

This Fall’s Monarch Migration

If you are keen to witness this fall’s Monarch migration at Cape May, respond to cold fronts. When temperatures drop and you need to find your flannel PJs or a comforter, seriously consider making the journey to Cape May the next day. These cool winds from the north and northwest blow southbound migrating birds (and butterflies) out to the coast. Once migrants reach the coast they hug the land and follow it south (sometimes working hard not to be carried out over the treacherous Atlantic Ocean waters). These migrants reach lands end at Cape May Point.

Winds That Bring Monarchs to the Tip of the Cape May Peninsula

Often, the strong winds that carry migrating Monarchs to the tip of the Cape May Peninsula are winds that are not  conducive for crossing the Delaware Bay (strong winds that could blow them out to sea instead). Their numbers may build as they wait for gentler and more favorable winds to cross the bay. During these periods you can find them nectaring on Giant Sunflower and Groundsel-tree (Baccharis halimifolia) along the trails at the Cape May Point State Park and on Seaside Goldenrod in the dunes.

conducive for crossing the Delaware Bay (strong winds that could blow them out to sea instead). Their numbers may build as they wait for gentler and more favorable winds to cross the bay. During these periods you can find them nectaring on Giant Sunflower and Groundsel-tree (Baccharis halimifolia) along the trails at the Cape May Point State Park and on Seaside Goldenrod in the dunes.

Winds That Help Monarchs Cross the Delaware Bay

These gathering Monarchs wait for gentle tail winds (winds from the north or northeast) that will enable them to safely cross the Delaware Bay. Such winds often occur several days after a cold front has passed. In the meantime, while they are gathered at the tip, enjoy evening roosts (sometimes holding hundreds or thousands) and return at first light to watch “lift off” as they use these gentle tail winds to continue their migration.

There are many opportunities to learn about Monarchs:

NJ Audubon’s Calendar filters for all their Monarch events:

- Monarch Monitoring Project Drop In(s) at the Nature Center of Cape May

- Monarch Monitoring Project Drop In(s) at Triangle Park (in Cape May Point)

- Monarch Tagging Demos

The Cape May Point Science Center is also offering Monarch Butterfly Tagging Demonstrations using a solar-powered GPS device as part of their Project Monarch. These demonstrations will occur on Thursdays (September 19 and September 26) at 1:00 p.m. and on Saturdays (September 21 and September 28) at 11:30 a.m. Follow the Cape May Point Science Center’s Facebook page so you don’t miss these and other great learning opportunities.

Do not miss the September 29th Monarch Festival at the Nature Center of Cape May.

On Facebook, follow Cape May Monarchs – this page occasionally informs about Monarch migration, roosts, etc.

The Monarch Monitoring Project home page shares a lot of the history of this project.